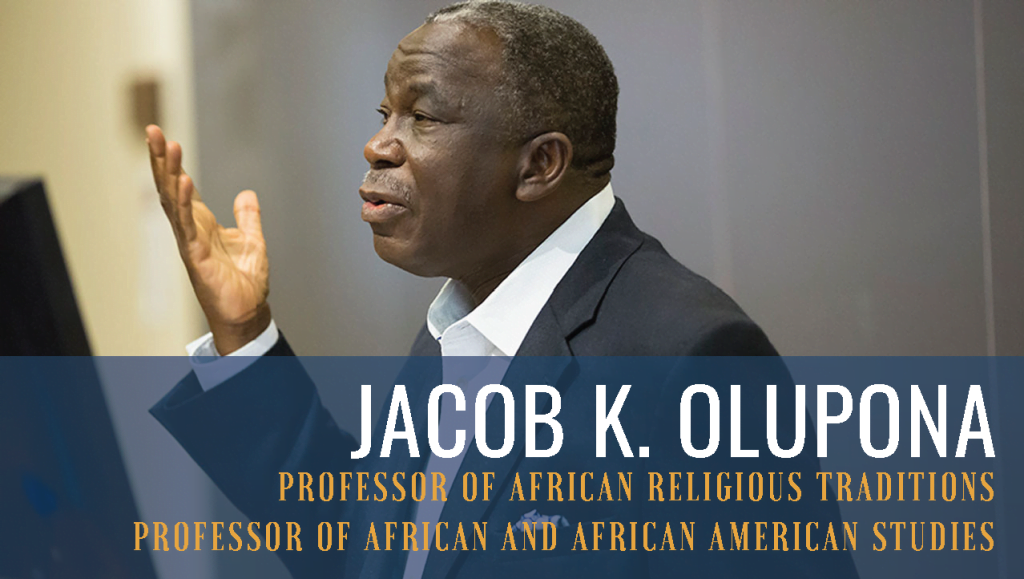

Even a casual conversation with Prof. Kehinde Jacob Olupona feels like taking a graduate course at Harvard. That might be because Prof. Olupona is a renowned professor of indigenious African Religion and Tradition at the Harvard Divinity School, and Professor of African and African-American Studies in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, University of Harvard. Widely decorated in academic circles, Prof. Olupona has also received numerous non-academic awards, including the Nigerian National Order of Merit, the highest award bestowed on a civilian by the Nigerian government. Prof. Olupona’s humble demeanor masks the greatness of the man whose groundbreaking work in comparative religion continues to make waves around the world. Nigerian Parents Magazine sat down with Prof. Olupona to hear the great scholar’s story and bring it to Nigerians the world over. Enjoy the interview.

NPM: Professor Olupona, thank you very much for joining Nigerian Parents Magazine (NPM) today. Let us start with trying to get to know you. Give us some background about yourself, where you grew up, a little bit about your family, your upbringing and how you got to be where you are today.

OLUPONA: Thanks for the invitation to be part of this conversation. I am Jacob Kehinde Olupona. I am from Ondo State in Nigeria. My father was born in a place called the Ute near Owo. My mother came from a town called Okeigbo, also in Ondo State. The two towns are at the opposite ends of the state. If you come to Ondo State, entering from Ife, and cross a river called Oni, you are in Okeigbo, my mother’s hometown. Okeigbo is famous for being the city where the writer, Chief D.O. Fagunwa, who wrote a lot of work in Yoruba literature, was born. Fagunwa was married to my aunt, the last child of my mother’s parents. Then as you move across there, you are on your way to Benin, and you now branch to Ute, my hometown, my father’s place.

My father was the headmaster of the primary school in Okeigbo. My mother was also there teaching. They met and got married and I was born. As you probably can tell from my name, I was born a twin, ibeji as we call it. In Igbo culture, they call it ejima. I was born into my grandfather’s family, a Christian family. They were one of the earliest converts to Christianity. I still recall the house where my grandparents lived and where I was born.

On my father’s side, my grandfather was also a staunch Christian. I usually refer to them as evangelical Christians, not the type we have today, but evangelical Christians who were members of the Church Missionary Society (CMS). They took Christianity seriously, even though traditional religion was very strong at that time.

My parents were committed Christians, to such an extent that my Oriki (the epithets and names and places that relate to people’s lineage, which is very important for the Yoruba people, also includes the Christian Oriki. That is very important to me. We see here the creativity of our people, but it is also a tradition that we cherish because it talks about you or your being as highly ontological. It is not just about knowledge. It’s also about knowing who you are, which is very important. That’s why I am very happy with what you are doing with Nigerian Parents Magazine. You are telling the stories of Nigerians, telling the world who they are. Some people cannot say who they are. They do not have good stories to tell about their parents, which is very sad.

I am not generalizing, but I am saying that you do have cases like this. When we were growing up, we were always advised to remember the son or the daughter of whom we are – our parents, grandparents, and lineage. You live for yourself, but you also live for your family. You do not want to spoil that name. The name is worth cherishing. Therefore, I am very proud that on both my father’s side, and on my mother’s side, this was very serious.

I grew up in the town of Okeigbo. The exciting thing about it was that because my mother or my parents gave birth to twins, they had to find a way of taking care of them. My granny had a niece who did not have a child, the wife of a very powerful chief in town, and who was not literate in the Western sense. So, they asked her to come and join my grandparents to take care of the twins. The woman would take me to where she lived in a place called Okejege in Okeigbo. She would take me in the morning after my mother had breastfed me, and bring me back in the evening. I got interested in tradition because she raised me as a twin, as ibeji.

If you are familiar with Yoruba culture, you would know that ibeji’s are sacred beings. Ibeji is as sacred as the Obas. Therefore, he raised me there. He will make sure that they do the Ibeji ceremony. They called children around to come and dance and sing, and it was almost a weekly event. Therefore, I was socialized into understanding the culture, understanding the tradition.

I used to tease my parents that they were missionaries. My parents moved to the city next to Okeigbo called Ondo. It was there that my father received the call to be a priest. So, he decided to go to Ibadan to be trained as a priest in Anglican Church. When he came back, he was transferred to another important town called Ile-Oluji. That was where I now started doing serious schooling. I went to primary school there; I went to secondary school there. It was from there that I went to the University.

Where did I go? I went to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. It was after the Civil War. Therefore, I grew up in Ile-Oluji, so to say. God blessed me with one thing: I am always curious about culture and tradition.

My parents did everything humanly possible to protect me from the outside world, and you know that the Anglican Church, the parsonages where the pastors live, is usually walled. Part of it was to protect people like us from mixing with the so-called pagans. Therefore, I took an interest in everything that I came across. I am doing this work with another young Nigerian who also grew up in this place. He has now converted; some of his children are priests. The other person is Wole Akiyesoye, who lives in Lagos. He worked for an oil company and he is a brilliant young man who writes beautifully well. By the way, he wrote a review of my book “In My Father’s Parsonage,” which I wrote many years ago to deal with my pain after my father died very young.

As a young man, my father wanted me to study with his teacher, who was Canon Edmund Eleogu, who taught in Ibadan and was part of the Anglican Church. He was a no-nonsense man and later became a professor. I had a cousin who my parents raised; he is a brother – Dr. Dupo Olupona. My father sent him to the University of Ibadan to study medicine, and people wondered why he sent his son to study Religion; at the time, they called Bible Knowledge and his nephew to study medicine. Here I am now; the boy who was sent to Nsukka to study Bible Knowledge is a Harvard professor. There is no other way to see it except to thank God. It is His work. I am not saying it in the way we hear it from our compatriots in Nigeria, I take that statement seriously, and I am humbled.

Nobody who went to Nsukka from 1971 to 1975 will ever forget a young man called Jacob Kehinde Olupona. They all knew me as Kehinde. I was one of the youngest and into so many things, politics, sports, etc. The truth is that the Nigeria we are seeing today is quite different from our Nigeria of those days. We explored. Yeah, we knew there was a difference between the Igbos and Yorubas. Yeah, Yorubas were part of the Hausa-Fulani that fought the civil war, but the Igbos were not hostile to us when we went there to study.

Years ago, I was somewhere in Ife or Ibadan, and they were arguing about Nsukka, and they thought it would be impossible for a Yoruba person to be a member of the students union in Nsukka. I was angry, and I said to them, who is telling this? Even before my set, there was a set before me; Akinsogbo was a member of the executive. He came immediately after the civil war, and I came a year later; he was a student union member. After me, another Yoruba boy was a member of the student’s union. That was Nigeria of our days. Can we bring it back? That is my concern. A typical Nigerian is not worried about who governs and if they can deliver.

What is the purpose of ensuring that your relative becomes the president of Nigeria, and what you’re going to have in exchange for voting him in is debt? There are times when I feel that maybe there is a system of sending all of us to the psychiatry in Nigeria to have our heads examined. I have not been able to explain why we are this bad at governing ourselves.

They talk about leadership and so on. What about those who are following the administration? Let me give you one example. I talked to a group of journalists after the Anambra State election of Prof. Soludo. I referred to an incident that happened; when a poor woman was asked to take a bribe. They were distributing money, and when they got to this woman, she refused to take the money, and it was 5000 Naira. I asked the journalist: “you folks give prizes and awards for good behavior. Why was this woman not elected woman of the year in Nigeria to send a message”? We still have some good practices; we still have honest people. That story will be told to the whole world in a civilized community. This woman did not want to mortgage her conscience or sell the future of her children and grandchildren.

Going back to my school, I did very well at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. It will probably be interesting that 46 years after I left Nsukka, the school invited me back to give me an honorary degree. The ceremony was a year ago, on June 12. Some people were surprised I went because everybody said people should not go to that area. The place is dangerous, and I knew that. My wife was shocked when I told her that I was going to Nigeria tomorrow and I had my ticket. I wanted to go to the graduation ceremony to get the honorary degree, which for me is a confirmation that at least I did some valuable things there. In addition, I have represented the university very well. The university did not say because I am a Yoruba, they would not give me the honor.

NPM: I read somewhere that you brought your children up both in the Nigerian and American way. How were you able to keep them grounded in both?

OLUPONA: First, it is God’s work. I claim that God has been merciful to us. Again, it has to do with the family heritage. If I have one fear for my children, something in our genes compels us to have unconditional love for other people. If you do, God will bring issues before because he wants you to solve them for other people. It is not about you. I am starting with this by saying that family values are critical. We exposed them to many things from my father’s and from my mother’s sides from day one. We try as much as possible to make sure that they know their people, just as my father did to me. We try to let them know that kindness is essential. You must be kind to people. We also let them know that honesty is necessary and there is no substitute for it. Mind you; it is not just in talking. They also see you doing it. They understand clearly what their parents will never do.

This socialization and upbringing are vital. Then, of course, so is the language. You see, when you bring kids here, they tend not to speak the language because of peer influence and so forth. We have no other thing but the Yoruba language in my house. We speak the language to the point where my children will ask me to speak the Yoruba language to them. They make me feel guilty when I do not speak it. It is part of socialization. I am not saying this because I am ethnic, but intellectually, I know it means a lot. There is no better way to express oneself than in your mother’s tongue. It has no substitute. Sometimes, when I read the English Bible and do not get a good answer to what I want, I go and take my Yoruba Bible. I have my father’s Yoruba Bible and Hymn Book. I am still searching for where they packed my grandfather’s Yoruba Bible. The Yoruba Bible gives me answers that I could not get in the English Bible.

As I read the Yoruba Bible, I think about our culture, nation, and people. These kinds of ways of bringing children up are crucial. So, when you look at what is happening today in our Nigerian society, including children hiring people to write their essays for them in high school and in the universities, and doing it with their parents’ knowledge, you weep for Nigeria.

My family, we are not saints; we have our issues too. Then I must also mention the role of the wife and the mother, my brothers, this is important. They are often not tangible roles, and it is not about money. The man puts down the money and thinks he has done the work. You have done nothing.

Let me tell you a story. One time when I had a birthday, my children went to town with it. You would think that their father was a saint. When they finished with the celebration, I said thank you very much. Thanks for recognizing that I played a significant role in your lives, but you must remember that we got all these things done because your mother cooperated with us. Your mother was the one who went to all your sports events, even when there were problems; when black kids go to school, there is usually a problem. They will not call me because they know I will come there to cause “wahala” and demand that we are treated with respect. Their mother will go and take care of these things and solve the problem.

The role of wives and mothers is essential. We, as Nigerians, do not recognize that. We are reading about violence against wives. That is becoming rampant now in Nigeria, and it is mainly, I think, caused by the severe economic crisis. There are forms of misplaced aggression, and women feel the heat. It is getting out of hand in Nigeria.

In fairness to Churches and Mosques in Nigeria, it is not true that they do not talk about these things. They do. However, the economic crisis is also a problem.

Therefore, we raised them to take seriously all matters I just mentioned, and it is not all about Christianity. It is not about that. It is about full humanity, to raise them as human beings that respect and recognize others.

The two Cardinal principles that hold us as Christians are duty towards God and our neighbors. What I see in our case is that we love God, but we do not love our neighbors. If you love God and do not love your neighbors, you have not fulfilled the laws. Therefore, you are not a Christian. Our people say they love God, which I doubt. You cannot swear with the Bible and the Quran, yet you are looting the treasury. You know that the money is for constructing roads, building hospitals, and helping people get jobs, and you say you are a Christian and you love God. I have problems with that. We raised our children in ethics and values that we understand and follow. We sent them to good schools, and they did not disappoint us.

NPM: I would be remiss if I did not follow up on this question and something you said about the language. I am a linguist, and my doctoral degree is in linguistics. One of the things that I have grappled with, especially within the Igbo community, is something you touched on, which is trying to make sure that the children that we are bringing up here do speak the language. Yoruba and some of the other ethnic groups are doing better in that area. Could you be more specific on the steps that you and your wife took to get them to that point where they are the ones asking you to speak Yoruba to them? What did you do?

OLUPONA: First, two of my children were born here in America. Then we went home, stayed home for a few more years, and returned here. Our first child was born at home, and she stayed with my parents until we got back and decided to come back to the United States. The first principle is that when you are home, yourself and your wife, you speak your language and the language you speak to the children and encourage them to speak it to you. If they see you doing it, they would want to do it. If the older ones pick it up, the junior ones will follow. What happens in some cases that I know is that these parents are deliberately telling their children not to speak their language because they are equating it with illiteracy. We have had some places where we went to association meetings where people said “do not speak Yoruba to our children”. I see it as self-destruction not to speak your language to your children. It is total ignorance. I have some cases when I go to the store or somewhere with my children, and they want to say something in English because they do not want the other person to hear it; Yoruba is the language they speak.

You probably know that we have a policy here at Harvard that if one or two students are interested in a particular African language, we will get a tutor to do it. Harvard University African studies has the most extensive African language program in the world. For example, an Igbo Nigerian teaches Pidgin English at Harvard, and the Pidgin English class at Harvard is large. It is one of the main classes offered here at Harvard. An Igbo man who used to teach the Igbo language teaches it. Language is important and has nothing to do with illiteracy. Otherwise, why would Bishop Ajayi Crowther translate the Bible into the Yoruba language? He also helped in the translation of the Bible to Igbo. He was part of that group. I think, if parents want, they will get it done.

To be continued