From a troubled youth working on the streets of New York City to owning a fancy restaurant in

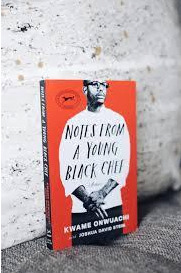

Washington, D.C., 29-year-old Kwame Onwuachi’s star is still rising. This year saw the publication of his first memoir, “Notes from a Young Black Chef,” and in the upcoming months, it’s set to be adapted into a feature film, starring Lakeith Stanfield and financed by A24.

Mr. Onwuachi isn’t your ordinary twentysomething African-American male. From working at McDonalds to starting the ill-fated Shaw Bijou—an upscale restaurant in Washington, D.C. that would close less than three months after opening—he’s experienced his fair share of ups and downs. Mr. Onwuachi, owner and executive chef of Kith and Kin, located at the Wharf in the InterContinental Washington D.C., carries himself with a humility that belies his notable achievements, and that can only be properly contextualized though an understanding of his life struggles.

Mr. Onwuachi grew up in a financially struggling family in the Bronx. Working alongside his mother in their small apartment, helping her to peel shrimp and cut vegetables, provided the seed for his fascination with fine food. Now, Mr. Onwuachi is helping to redefine Afro-Caribbean cuisine from the heart of the country’s capital.

Nigerian Parents magazine recently met with Mr. Onwuachi at his 3,500-square-foot restaurant, which boasts sweeping views of the Potomac waterfront. The first thing that Mr. Onwuachi presented was the restaurant’s menu. Right away, it was obvious that he takes great pride in the curation of the restaurant’s dining experience. “I wanted to cook for my people, and it is from the heart,” Mr. Onwuachi said.

The menu is an impressive assortment of Nigerian and Afro-Caribbean cuisine that’s a reflection of Mr. Onwuachi’s heritage—namely, his family’s roots in Jamaica, Nigeria, Trinidad, and Louisiana’s Creole country. “Now you can have oxtail, jollof rice, suya, and curried goat in a luxurious environment,” said Mr. Onwuachi.

Mr. Onwuachi graduated from the famous Culinary Institute of America before then going on to appear on the reality TV show “Top Chef.” If you’re ever in the D.C area, do not pass up the opportunity to dine at Kith and Kin and experience its vibrant fusion of cuisines. From the Nigerian-inspired jollof rice and suya to the Caribbean curried goat, just one taste of Mr. Onwuachi’s flavors will arouse your sense of nostalgia.

Is Sending Your Troubled Child to Nigeria Always Good?

Kwame Onwuachi was sent to Ibusa, a community in Delta State, Nigeria, at the age of 12. His mother told him it was just for the summer. Indeed, Onwuachi expected to come back to the United States before school resumed, but his mother insisted that he stay in Nigeria until he learned “respect.” We chatted with the most celebrated chef in America about how his two year stay in Nigeria affected him.

NP: How did staying two years in Ibusa with your grandfather impact who you are today?

Onwuachi: When my mother told me that I was going to Nigeria for the summer, at first I thought I was being punished for something, maybe for recently breaking a cutting board. But the more I thought about it, going to Nigeria to see granddad wasn’t such a bad idea. I spent two years there, and when I came back to New York at the age of 12, I quickly started to appreciate the experience I had.

NP: You started school at Santa Maria College in Ibusa. How does your experience at Santa Maria compare to school in the United States?

Onwuachi: Oh, wow. It was clearly very different. The Nigerian method of discipline quickly became clear to me. For one, talking back to your teachers wasn’t an option. But I also quickly learned that in Nigeria teachers don’t see you as a problem. They see you as a young person who must be given both an education and taught the lessons of life. Soon, I started to feel more joyful than ever, more than I ever did in the Bronx.

NP: You write in your book, “Notes from A Young Black Chef,” that your mother said you would stay in Nigeria until you learned “respect.” Did you learn that respect?

Onwuachi: Ibusa taught me to appreciate the little things around me. For example, the gathering of elders that my granddad presided over to settle local disputes, or settling small claims in the village, thought me that people had respect for each other.

NP: Your granddad spent the greater portion of his career encouraging the African diaspora to feel pride in their heritage. How did your granddad’s role impact you?

Onwuachi: I loved that I had the opportunity to connect with my roots. I wish more people could have that same opportunity to make that kind of connection.

NP: What advice would you give to a child who may be sent to Nigeria, like you were by your mother, in order to learn respect?

Onwuachi: It depends on the situation, because each situation is different. It also depends on who you have in Nigeria to take care of you. In my case, I had my granddad. I enjoyed staying with him very much. I remember the day I left to come back to United States and he said to me, “You can’t take this land with you but your ancestors will never leave you.” That is good advice.