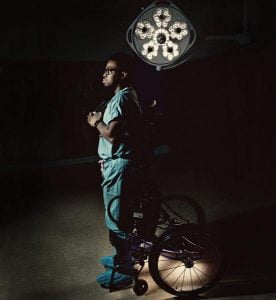

Disability is not Inability ~ Dr. Oluwaferanmi Okanlami

In today’s technologically advanced world, the search for anything or anyone begins with Google. So, when many of our readers asked us to find and feature Dr. Oluwaferanmi O. Okanlami, our first step was to search for his work on the powerful search engine, Google.

Dr. Okanlami is the young and courageous Nigerian-American doctor who has thrived in the face of impossible odds. Delightfully, upon further investigation, we discovered that Dr. Okanlami epitomizes the longstanding Nigerian belief that when family values are connected to faith, an individual becomes even stronger, in spite of adversity.

Oluwaferanmi O. Okanlami “Dr. O” was born in Nigeria before immigrating to the United States with his parents at a very young age. His academic excellence earned him the opportunity to attend the prestigious Stanford University where he majored in pre med within the interdisciplinary studies program in humanities. At Stanford, Dr. Okanlami ran track and field for four years. He was team captain for the last two years and attained All-American recognition.

He further attended the University of Michigan where he completed his medical degree. Dr. Okanlami moved into an orthopedic surgery residency at Yale. At the beginning of his third year at Yale, Dr. Okanlami suffered a spinal cord injury, which left him paralyzed from the chest down. With rehabilitation and determination, he regained some motor function. Even in the face of adversity, Dr. Okanlami never lost focus. He joined the ESTEEM program at Notre Dame and earned a master’s degree in engineering and completed science and technology entrepreneurship.

Currently, Dr. Okanlami is Assistant Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He also has a joint appointment in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. In 2017, he was awarded one of Michigan’s Forty under Forty awards by Mayor Pete Buttigieg.

In his interview with Nigerian Parents Magazine (NPM), Dr. Okanlami discusses faith and family as the most important reasons for his excellence in academics and his continued ability to thrive professionally. He admits that the challenges he faces are real, but he has eyes set on the prize. We invite you to read the story of yet another Nigerian-American shining star doing extraordinary things in the Diaspora.

Nigerian Parent Magazine (NPM) Interview with Dr. Oluferami Okanlami

NPM: Dr. Okanlami, thank you for speaking with us today. One of our readers recommended we find you and speak with you to hear about your incredible courage. So, let’s kick this off by asking – Who is the man Dr. Okanlami?

OKANLAMI: Thank you very much. Good afternoon. My name is Dr. Oluwaferanmi Oyedeji Okanlami. Currently, I am an Assistant Professor of Family Medicine and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Michigan Medicine. I am also the Director of Medical Student Programs in our Office of Health Equity and Inclusion, the Director of Adaptive Sports at Michigan Center for Human Athletic Medicine and Performance. And I am the spokesperson for Guardian Life in our equal and able campaign trying to demonstrate that disability is not inability. More importantly, I am the son of Dr. Olufemi Oyetunji Okanlami and Dr. Olubunmi Abosede Okanlami and the younger brother to a Juris Doctor Olubunmi Oyepeju Okanlamiand the father to Alexander Oyedeji Paich Okanlami.

NPM: Thank you for that wonderful introduction. I don’t know if you have heard much about the Nigerian Parents Magazine. What we do is strive to provide parents with tidbits on how to raise well-adjusted children. You are obviously accomplished and well-adjusted. So we figured we would talk to you a little about your upbringing. Could you talk to us about your upbringing and how your parents influenced you and anything our readers would read and say, “I want to bring up my child to be like Dr. Okanlami”.

OKANLAMI: Well, I would say then that the person we should have on this interview is Dr. Olubumi Okanlami because of my two parents, she is the one that still remains. They are the ones that should be given all the credits for the work that they have done. But I will do my best to try and represent what I feel my education and my upbringing was based on my parents’ rearing to give a good picture of what it was.

I was born in Nigeria. We moved to the States when I was three. My sister was about five or six. We first moved to Maryland when we came here. Both of my parents were physicians and they had to redo their residency training in the States. And they did that at Howard University before going on to do their postgraduates at John Hopkins and Georgetown where they did pediatric critical care and neonatal critical care respectively, my mother and my father. They then moved to Indiana where they enrolled us in private school in South Bend Indiana. Education has been the most important thing that our parents have instilled in our lives. They say that education is something that will provide you with the tools to be able to take care of yourself and your family. And it is something that one else can ever take away from you. So we have been enrolled in magnet schools, the talented and gifted school in Maryland and we ended up going to a private school in South Bend Indiana. My sister ended up attending Catholic school for high school and I went off to a boarding school back in the East Coast called Deerfield Academy.

So, I will say that with respect to what I think may be of interest to your readership, growing up as a multicultural family, being Nigerian by birth, and being Nigerian by how we were raised, but living in American culture and being exposed to other people who had different ideas of what was right and what was wrong, what was important and what was not, our parents made it very very clear that what they said in our house was what goes. We don’t care what your friends’ friends are saying, what your friends’ parents are saying, what they are doing. And it was something that was ingrained in us. The important part of when we were first in Maryland is that we had an opportunity that we were raised in a group. So, there were two other families that had two and three children each that raised us somewhat like a little village. And we spent time at one house or the other when the parents would be working. They would shuttle us back and forth from house to house. So we had a community of Nigerians that were there being raised with. All of us now are still in touch and between the ages of about thirty and thirty-nine. We are all doing our various things across the country. My sister who is the second oldest of the entire group, she is now working for CLP Legal in Nigeria, a law firm there, after completing law school here in the United States and then going back there and doing Law School in Nigeria. All the way down to the youngest one of us.

So, as I said that education was the thing that was most important in making sure that we also understood our Nigerian heritage, where we came from. All of us understand Yoruba. We all still speak our language now. While you may tease us for how our accent sounds, that’s because we have lived here for most of our lives, but we can speak it. We can understand it. So that is something that was always made as important, right? Sometimes you come to this country and people lose the sense of where they came from. They don’t always continue with the traditions that we practice back at home, and it becomes a bit easy to feel removed from that culture. But that was something that first living in Maryland and then having family living in Houston, Texas taught us. I call Houston, Texas, the Nigerian Plymouth Rock sometimes because you know when you’re out there, you can still get out, get Agege Bread. It’s something that we were able to stay connected in very different ways. I’ll pause just because I could talk forever. But I want to make sure that I’m tailoring whatever it is to what you’d like to hear.

NPM: Thank you Doc. Obviously, you have a lot of courage, and discipline. And that’s what it takes to get to where you were today. Right? How did you develop this kind of extraordinary courage to propel you to where you are today? Is it something that your parents instilled?

OKANLAMI: First of all, that’s very, very flattering that you would say that. But I take no credit for any of the things that have been happening in my own life. I first give credit to the Lord for providing the opportunities for me to be where I am now. And for my parents that were the ones that instilled this in me the work ethic and the understanding that anything is possible, you know, through Christ. That’s truly the basis for where this comes from. And my parents would also not take credit for any of the successes that we have had. But it’s all due to the glory of the Lord that has happened. So I will say that they were amazing examples, however, of how to live a life based on the word of the Lord. And they made sure that was the central piece. But then living their lives and watching what they did. They were wonderful examples of that in which they treated everyone the way that they should be treated. They treated everyone with respect. No matter if he was a janitor, no matter if you were the CEO. They treated everyone with respect. They demonstrated that hard work was the thing that you could do to make sure that you gave yourself the best opportunity. They didn’t cut corners, they didn’t make excuses. And throughout all of that, they still took care of each other. They still love their family. They still took care of their family in Nigeria. They still took care of us here. And it was something that no… no struggle was too much to handle, because the Lord wouldn’t give you more than you can handle.

So, that was something that I saw in their own lives over and over and over again, such that as we all became young adults ourselves, we had no excuse because we saw families that uprooted the entire family from Naija to come to the states to redo residency work that they’d already done in Nigeria. Imagine raising Children in a foreign place, sending us to schools, juggling different jobs, moonlighting, doing all sorts of things just to take care of us, sacrificing things themselves to then make sure that we had the things we needed. That was something that we saw over and over and over. So when people talk about my own courage, I say you’ve seen nothing until you see the lives of my parents and the things that they have done. My own courage pales in comparison. So, as I said, I’m flattered and humbled to hear you say that. But when I started this call, I said, I’m the wrong person to be speaking to you. You want to move this story? You should be speaking to my mother.

NPM: I think we’re probably will, at some point. So have you always wanted to be a doctor from the get-go or was this something that you decided along the way when you found your path?

So you know, I say that I used to say things like, I want to be an astronaut. I wanted to be a paleontologist, but I’ve always said doctor, in that mix. So my mother has a picture, apparently that I drew when I was a young, young boy, of me with my family and I had a stethoscope and I was holding doctors instruments. But always for as long as I can recall, being a physician was something that I, I said, was my goal. And it helped that I had two physician parents. I had multiple aunts and uncles that were physicians. And so I was able to see what the lifestyle was and see that it wasn’t all glamorous. But I still enjoyed what aspects of medicine I saw my family demonstrate.

Now I tell you, my sister is, as I said, is two and half years older than me, and she’s a lawyer. So just because you see doctors and your life doesn’t mean you end up going that way. Sometimes you go the opposite direction. But it was something that was an opportunity for me to see what it was that they did. And then it exposed me to it. I have opportunities because they were in medicine. And so I was able to then investigate that further myself and choose that. That’s where I wanted to go.

NPM: Great. So you were born in Nigeria as you indicated. Whereabouts in Nigeria?

OKANLAMI: So I was born in Lagos.

NPM: Then you came to the States when you were 2 years old. Okay, so how has it been? At two years old, you probably don’t have a lot of memory about what happened earlier on your arrival.But from what you’ve heard from your parents and others, there’s always a story about you know, when kids come here, the struggle and all that. What was the experience like?

I remember that first time. What happened was my mother came over and she came and she did her US MLE exam. I remember she ended up living in Minnesota, in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, with a family friend that had already come here first to take her exams while my father was in Nigeria working with two young children. So that’s sort of the first example of the amount of sacrifice that it sometimes takes to be able to pave a way for your family. Right? Then, they both came and moved to Maryland. I remember stories about how they had friends and one friend that worked in a furniture store that helped us get a mattress on layaway. And that was the one mattress that we had in our one bedroom apartment for a family of four. I’m not sure if my grandmother or great grandmother came with us at that time or not. But there were a few of us living in that house at that time, with this mattress on layaway, with these two physicians, right? So people would think you have two doctors or because your family lives in the United States, therefore, you have everything made for you. But I heard the stories of that time, of all the things that they had to scrape together to be able to then make sure that we have the things needed. Now I don’t ever remember a time throughout my life I felt like I lacked for the things that I needed. Right now, even though now looking back and hearing the stories, remembering these things, you can imagine what things your parents sacrificed. I never remember feeling as though we didn’t have, even though there were plenty of things we didn’t have that I know other families had. And as we grew up, they made it very clear that they were providing us with the things that we needed. And just because there may have been some things that we wanted, it doesn’t mean that you get everything that you want and it doesn’t mean that you need everything that you want. So that also put sort of money and amenities and perspective to us such that we didn’t take for granted the things that we had and that we knew that just everything that glitters isn’t gold. And so it’s important to make sure that you know what’s important in your life. And, as I say, being a broken record going back, faith and education and family were the sort of a foundation upon which they built the life that we then have. So you know someone looking back, may say, “oh, you were born with a silver spoon in your mouth, having both your parents as doctors, having your parents living in the States. But I know that as I saw how they took care of us and how they spent their money, I didn’t know these things until later in life. But every dime that they were making was going towards us or was going back home for all the people back home. Both of my parents were the eldest of six. And so I knew that there were other people as well that were looking to them. And then we had people that won the visa lottery. They then came to the United States and stayed with us. You know, uncles and aunts and different people came one after the other. You know, my mother’s youngest daughter, our youngest sister, still lives in Maryland right now. You know, she was someone that was raised almost with us as a sister, even though she was my aunt, you know, and seeing the way that they paved the way, not just for their children but for their siblings as well. And how that is the culture of how we take care of one another in our family. It’s not seen as an obligation. It’s just seen as what it is that we do, right. It’s not done begrudgingly, it’s just part of our culture of how we take care of one another. And so that is something that I saw from a very young age that now you know, I’m starting to get to that generation. It’s now becoming my responsibility to make sure that we start to think about who it is that we need to be supporting and taking care of in our families.

NPM: So you had a spinal injury when you were … I think in your third year at Yale, right? Could you speak a little bit about how that impacted your life?

OKANLAMI: Well, you know that question about my spinal cord injury and how it impacted my life? I feel like the answer continues to develop because, at the immediate time, the way that it’s physically impacted my life. I went from being an All-American athlete from Stanford turned orthopedic surgery resident, going through medical school at Michigan to then residency at Yale. And as you said, it was my third year, and I was just starting to really become more of an independent surgeon. And the immediacy of this injury rendered me paralyzed from my chest down with minimal use of my upper extremities. And it stopped my professional and my personal career right then and there. Now all of the things that transpired from that point about six years ago, to now. Only the Lord could have predicted, and actually knew what was going to happen. Because what it then did was, it literally and figuratively stopped me. It stopped me and it gave me time to then refocus on what it was that was important. And to make sure that I knew who it was that I was living for and who was guiding my life. And so it gave me time to then reflect and to pray. And that was something that I don’t know where I would be today. I mean this honestly. I don’t know where I would be without that accident. Not that I thought I was going down some bad path. But the perspective that I now have, given that I had what I thought were my abilities, right, my little abilities physically, you know, professionally to be a surgeon that handled complex musculoskeletal injuries to become someone that couldn’t even urinate on my own or tie my shoe or get up on my own. That was very humbling. And it reminded me that none of the things I had did I deserve. None of the things that I have, did I get because of just my own hard work? And so it continued to give me a perspective that says once again the Lord is the one that we should be sending our sides towards and then knowing that I am no better than any other person in this world. No matter if I am taller, shorter, black or wider, strong or weak or whatever it is that I do. And so it has helped me to now focus my personal professional efforts to create equity and access for all, regardless of what it is that they may do, what they may look like or what opportunities they have. The goal is trying to make sure that all people have equal access and opportunity, something that I know that I was blessed to have an abundance of opportunity and resources, more than many people have had. And that to whom much is given, much is expected. So I thought, but I felt that way before. But I think that this injury definitely put in me the ability to realize that tenfold, and to say that I now have an obligation and an opportunity to be able to be a voice for other people that may not have had as much of a voice, to create a path to access for people that have not had that access, and to demonstrate to people that one specific thing – that disability is not inability, but also that disability is just one aspect of diversity and diversity of thought, diversity, of experience, of opportunity. And that’s when we respect all people for what it is that they can contribute and recognize that everyone can contribute something, that’s how we really reach equity in terms of what we have. Because you never know what someone could do unless you give them an opportunity to do it. And you may have your preconceived notions about what it is that they can do. But until you give them that chance, you then allow them to show you what they can do. But they can, because I said earlier, they can do all things through Christ who strengthens them. So don’t let someone’s physical appearance, don’t let someone’s age, don’t let someone’s title or letters behind their name dictate how it is that you treat them or what you think that they could do. Just allow everyone to have the opportunity to show you. So that’s, I think, without getting into specifics, of physical ability for me, that’s how my injury impacted me. And I think what the lasting impression will be on what that means is correct.

NPM: Doc, this is inspiring. We do want to explore it a little bit more. I know that there will be people out there who have challenges and they are probably thinking it’s over. I’m never gonna amount to anything, I am never gonna do anything. And here you are, overcoming those challenges and getting to where you are. As I hear you speak and talk about this, about how disability is not a lack of ability and so on, could you talk some more about those challenges that you face and overcome everyday?

OKANLAMI: So I will. I’ll actually reframe that question a bit, because recently I had… I don’t want to call it a revelation, but I had experience that made me pause and think about how I was portraying my life. Because now, with social media and the ability for us to put our lives on display, I think that people that are able to paint the picture of the life they want others to see them lead, and with my desire to show that disability is not inability, I recently thought that, you know, I’m actually doing a disservice to people with challenges because they could get the impression that my life was without challenge. Or if I get depressed that I have overcome all of these challenges, then when someone who’s dealing with something themselves, rather than the feeling like I can get through this, what it sometimes creates is this idea that “why can’t I get through this”. “Look at him, he’s been able to get through it. Why can’t I?” And this is actually something that has been a contentious point among some of our generations now because a lot of us felt as though we didn’t get to see the struggle that our parents had, because I think an attempt to raise us and to make sure that we were resilient and that we knew that we could do everything sometimes, and this is why I say that it has been Thanksgiving dinner argument sometimes, sometimes my generation feels like our parents hid the problems from us. They didn’t tell us about how uncle did this. They didn’t tell us about how aunty said that. They didn’t tell us about some of the difficulties that happened in the family, because they wanted to make this picture that everything was okay. Now I don’t disagree necessarily with the intention behind it, which was not to burden the children with some of these things that are above their level of understanding. But I do think that that’s something, and if we don’t also acknowledge the difficulty in life, then we are misleading people to feel as though we’ve gotten to a point where we are without struggle, and that there will come a point where you overcome struggle and no longer will struggle come. You know, so recently, you know, I was listening to Scripture and the stories of, you know, David, and Saul, the stories of David and Job, the stories of Joseph, right, these stories of individuals that had difficulty throughout their lives. Most of Job’s life was a problem. You could talk about Joseph being thrown into a ditch, sold into slavery, thrown into jail right? These are things that have happened. And sure we know the end of these stories? But I think what’s important is to show people that still in my life, even though you may look at my life and I think he has overcome these things, to this day, I still have things that I go through. We are not promised a life without struggle, right? We know that if you continue to point towards that one thing that has guided us, if we continue to know that it is not by our strength alone that we get through these things, that is what makes you overcome. Because the struggle doesn’t go away. It doesn’t mean that all of a sudden you’re strong enough to then beat everything. It just means that you know that there’s something even stronger that is guiding your path. And I recently had, as I said, a revelation or realization that admitting weakness, admitting struggles, admitting that there are still things that I wasn’t good at, that there’s still some things that I need to work on, admitting that there are still problems that come into my life every day, do not then make me someone that is weak. I try to shy away from this whole inspirational sort of moniker because I don’t want people to look at my life as someone who has arrived. I don’t want to then have people use me as an example to say he has overcome these things and therefore you should, too. I actually wanted to be an example of something that’s human. He’s had struggles. He’s had success when we tell his story. I want to tell the story of the failures he’s had just as much as I want to tell the story of the successes, right. So I rattle off my accolades, but I didn’t tell you that I failed step three of my United States medical license. This is the first time I probably publicly said that. But that’s because I have realized that having to acknowledge the struggle that you have, allows people to actually see that that’s humanity, right? That shows that other people struggled too, and it doesn’t mean that they overcame that struggle. But they struggle. And some other person might fail step three, never get to be board eligible and not become a doctor. And that’s not the end of the world. Even if every single one of the family wanted you to be a doctor, if you don’t get to be able to be a doctor because you failed step 3 and you end up being something else, that is not a failure, right? And so that is something that while every single person in my generation understands when you come home with the 99% and you think you’re excited and happy and then your parents are like, “ah ah, 99?” Because if they don’t tell you to strive for about 100% you then become okay with the 72%. But when none of us are satisfied with the 99% because we’re pushing, pushing, pushing, that’s what allows you to have that fortitude, that work ethic to then get to a point where now, later on in your life, you can say, OK, that 98 might not be that bad. But now as a parent myself, am I over here saying okay for 99? So is the same thing I’m doing.

NPM: Doc, let’s talk a little about politics. I read that you know somebody who would have been the president of the United States, Pete Buttigieg. What do you think about him? Do you think it would have made a good president?

OKANLAMI: So, as we know, at this point, it’s a moot point for this current year. but I will tell you this, you know, and this is what I feel. I don’t know everything about every single one of those potential candidates. All right? And I don’t think any one of us knows everything about everyone of the potential candidates to be able to speak about what they would have ended up doing, right? Right? So the whole political process is something that I feel as though what we end up doing. you know… You talk about taking out the log in your eye before you take out the splinter in your neighbor’s. We then look at people’s lives and we scrutinize and we judge, and we make our own assumptions about what they’re like, without truly knowing them. What I’ll say about Mayor Pete, I call him Mayor Pete, is this. I know him as an individual. I know him as a classmate. I know him as someone who was in my church. I know him as someone that I worked with in city and county governments. He appointed me to the ST Joseph County Board of Health when I was back in Southend, Indiana. So what I can say to you is that he is someone that I trust. He is someone that I trust to then have people’s best interest at mind. He is someone that I know will put the interests of others in front of his own interest, and he is someone that will be thoughtful when it comes to handling situations. He is someone who is not afraid to admit when he’s wrong and will try to work on the thing that he is deficient in. He may not get it right the first time, but none of us does. Now the unfortunate part is that I think that the way the political landscape works is you’re not truly allowed to be the person you want to be. You have to try to conform in some way to the way the political world views you. So I personally think that at some point he will have a more legitimate chance of being the president of the United States. There are several characteristics that he has that may not be comfortable to all people right now. And some of those may be in sexual orientation. Some of those may be his age. Some of those may be the one issue that some of our community has not wanted to let go of which is the thought that he is not able to connect with right now. I will say… I shouldn’t correct that. I will say that nationally, the impression is that he does not seem to be able to connect with African American people.There are lots and lots and lots of situations where you can find people or groups of people, individuals that will be able to say one thing about a person and then it propagates and propagates. But I know Pete and I’m black, so I’m not willing to allow people to say no black people like Mayor Pete, right? I also would be very careful because I’m not going to say that some of the concerns that were raised aren’t valid concerns to raise. But what I will say is you find me a city in the United States of America this time that doesn’t have a problem with police on black people, and I will move there. So the way that things are handled, I still think that there’s a lot that needs to be done and to put it on one individual right now I think is unfortunate. And I think, knowing all the things that he was attempting to do within that community at the time that I lived there, yet the way that people in the community turned against him, I think was just very unfortunate. I am not saying that there may not be a valid reason on both sides, but that’s just the overall sentiment that he does not care, I think was ill positioned. The fact is that he could have done a better job. We all could do a better job. I will raise my hand first to say that I have a lot of things to work on.

NPM: Doc, tell us about practicing medicine in the United States and what your experience has been.

OKANLAMI: Uh, so, first of all, it’s ah, it’s an honor. It is a privilege. It is something that’s… even just today. So today is not one of my days that I have clinic, but I got a call from one of my colleagues that a patient of mine that she had seen on Saturday and a walk-in clinic, you know. He had some pain underneath his right rib and she wasn’t quite sure what it was. She got some labs and got some imaging. And then because of that, she got more imaging. And it turns out that the man has a portal vein thrombosis. So today, not my clinical day, but because I’m a primary care provider. I’m responsible for my patients 24/7. So I was able to then address it and put some more labs and imaging in and I referred him to hematology oncology, and started him on anticoagulation. And it was something that I looked at just the ability, through technology to be able to address that in real time. Before the CT scan was even uploaded to the computer, because she had been paged, she called me and we were able to address this. Now I say that because I have to call this man on a Friday afternoon and tell him with his CT scan that is going to be terrifying to him. He doesn’t necessarily know what portal vein thrombosis means. He just hears blood clots and thinks that that’s the end of the world, right? And so in medicine, you have this unique opportunity, obligation, privileged to then hold people’s lives in your hand, to be able to then give them hope or to be able to tell them sorrow. And you have to make sure that you handle it with the respect and with the delicacy that informs them, without alarming them too much, but making sure that they’re adequately informed about what it is that’s going on. So that is something that is a beautiful opportunity. Now practicing medicine in the States, I would say I never practiced medicine anywhere else, but I have gone back to Nigeria. I was actually just there a few months ago. We spent the Christmas holiday in Nigeria this year. I have seen wonderful health care in the States and I have also seen wonderful healthcare in Nigeria. I’ve seen bad health care in the States, and I’ve seen bad health care in Nigeria. So I also want to be careful that the things that I say are just my own experience because there are people who have been in this world many, many years longer than I have that will have a different set of experiences. Any comments that I make about healthcare systems here or back home are colored only by my own lenses and not everyone else’s. But I do know that specifically with respect to the fact that now I’m an individual living with spinal cord injury, the accessibility of health care in the States is something that has given me another level of privilege that I didn’t see being back in Nigeria. And, while I know that the intellect is there to be able to have the same access to care for whatever reason, and I won’t pass judgment as to why, but for whatever reason, the infrastructure is not the same. The opportunities aren’t necessarily the same, and that is a significant reason why, unfortunately, I’m not as comfortable navigating in Nigeria with respect to the fact that I use catheters to be able to urinate now. I use a mobility device to get around. I don’t have the ability to sweat, and so I overheat. I need to be able to then have cold water to pour on me or to drink. You know, These are things that, without consistent access to certain things that I see as just basics at times here, that are sometimes amenities in other places. Medical care in the States is something that I realize is another privilege, and this is now talking about two sides of it because you started to talk about practicing medicine and I talked about practicing medicine but inadvertently went right back to being part of the medical system myself. Which is something that, I think, is as an important distinction, that I am not a patient or a provider. I’m both and all of us are both. And I don’t want us to create this imaginary line that says physicians on this side, patients on that side because that’s something that we all experience. We all experience health and disease and struggle, and the fact that at times medical providers ourselves create this dichotomy between the two. I think that it distances ourselves from our patients in a way that’s unnatural, and it’s something that I have almost… It’s almost not really my choice to be able to embrace that, because when people see me, they first see a patient before they see the physician because they don’t imagine that someone who uses a wheelchair would be a doctor. And I’m blessed and ironically here I’m sitting. I’m actually sitting in one of my colleagues offices, but one of the things that she has on the desk… she has this on her desk (shows a medical magazine from Michigan). I don’t know if you’ve seen this.

NPM: Yes, yes.

OKANLAMI: Oh, this is one of our Michigan magazines from a few editions ago. And that’s me. That’s me on the cover, standing in my standing frame wheelchair in the operating room with a stethoscope around my neck. This article that they did in there was about the disability providers that we have here. My chair is Philip Zazove and he is deaf. I’ve got a group of other physicians and PhDs that we work with, our work is in disability access and health care and demonstrating to people that people with disabilities can be PhDs. They can be MDs. They can be Dos. They can practice medicine. They can teach, they can advise and that all of us need to recognize that disability is not something that happens to them. But it’s something that happens to all of us, and that we shouldn’t separate ourselves from that. So it was really an opportunity to be working here at Michigan, then have a group of people that recognize that and embrace it and support it. It is something that I have been blessed to be a part of both as a patient in this system and as a physician. That’s rendering care to others in the system.

NPM: We wouldn’t conclude this interview without asking you about childhood memories. Is there any childhood memory from Nigeria or from the United States that you would like to share with our readers?

OKANLAMI: Childhood memories? Yes. So I guess for the Nigerians, and maybe my family will be upset at me for this being the first memory that I think of, but I told you that we were all raised as a group and some of the childhood memories that I had when all seven kids will be together in the house and we would get in trouble and the types of things that you would have to do when you get in trouble, like getting on our knees and then put in our hands up. I think about those as memories because I think about the purpose behind some of the discipline that we have, right? And you… maybe we didn’t feel it at the time. But as you get older and older and older, you see that every single thing that was done, was meant to instill in us a level of respect, a level of responsibility, accountability. And those were things that now, as I grow up and as I am older, these are little things that I remember growing up. Like the fact that when I would go over to a friend’s house and I will clean up the table and wash the plates and just do without being asked. And they say… and they look at you like you’re from Mars, exactly. Those are the little things that create someone who other people look at and think “what is it that makes that person different?”. And it is the type of thing that you become proud of? You want to make sure that you continue to pass that on to your own children, and children’s children. Because while you may have complained about the fact that you were doing homework in the summertime and we were going to summer classes in the summer when you were fourth grade, now all your friends, without doing a lot of other things, that you see what that does in your own life, and it’s not that I wasn’t about to play, I’ve got to play. I played sports. I did plenty of things throughout my life, right? But because I was able to realize the purpose behind some of the decisions that they made, even though you may not have liked him in that moment, right, as you continue to mature, you saw that there was a reason behind the things they did. And that’s something that I will say, you know, in my Nigerian friends, it’s a consistent story amongst all of us that while we will joke that our parents were mean and strict and didn’t let us have as much fun as our friends, and made us work too hard, and said that you can only be a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer, right, all of these things, you then look back and you say, you know, “thank you”. Because just as I said, this whole conversation, no one’s perfect. Everybody makes mistakes. And while we may have thought as children, that our parents were supposed to be perfect, as you get older, you see that they were not. They were not infallible. They were not omnipotent. They were not omniscient. And so they themselves were just doing the best they could to raise children.

NPM: As we begin to wind up, what else have we not asked you that you think our readers would like to read about?

OKANLAMI: Oh, I mean, there’s way too much… there is one thing that I think I’d like people to read about actually. I talked about giving people an opportunity to show you what they could do. I think that … and then this is going to be potentially dicey, but I think that as Nigerians, we are still not as comfortable with disability as others. I think that we still see disability as a negative, even at times we see disability as a curse. We don’t always know how to embrace someone that is different when it comes to disability. And I want people to know that whether it is someone who has post polio, whether it’s someone who has an amputation, whether it’s some of the spinal cord injuries, or it is someone with anxiety, depression, bipolar schizophrenia, that we should not treat these people any different than we treat ourselves. We should know that as I said, everybody struggles with something. And so just because someone else’s struggle might be visible, just because they may be bipolar, just because they may have amputation, just because they may be obese or whether it is something that you can see, that it doesn’t make their struggle any worse than the struggle that you have. You may not be public about your own. You may not be willing to share. You may not be able to see your own, but we all have it, and no one of us is better than the other. So when it comes to that, I then asked, do we believe that everyone should have equal access to opportunity? And if we do, we should strive to make sure that we create that. If you ask yourself that question, every time a decision is made, every time our resource is allocated to something, I think it will change the way that we view the world. That would change the way we view each other because we have opportunities to help. I talked about how Nigerians are working hard all the time. They’re supporting the family. They’re supporting their friends and you’re making opportunities for other people that come behind them. This is an opportunity for our community to say that we are no longer going to then judge other people as less because of disability. We’re going to see the ability in everyone and make access for all people. That is one thing that I would say that I am trying to do myself. I am hoping that in the years to come, I will be able to do more work in Nigeria to make Nigeria as accessible as the United States is for me right now. I can’t tackle all things. But if I don’t think about physical accessibility, that is something that I would love to be able to create. More physical accessibility in Nigeria. And to take it down to even one level, my goal is trying to create equal access to physical and emotional health and wellness for individuals with disabilities in Nigeria and beyond. So, that is the one thing I would like to finish with.

NPM: Thank you for speaking with us, Dr. Okanlami.

OKANLAMI: My pleasure.

This Post Has 7 Comments

It was an honor interviewing Dr. Okanlami. What an extraordinary young man. What impressed me the most was his faith and his perspective on life. I encourage everyone to read his story.

The story of Dr. Okanlami is one story that should inspire all of us and our Nigerian-American children. It’s a story that tells a story of how physical disability does not mean inability. It’s a mirror of how seeming inability can actually push one beyond the limit of impossibility and with faith in God and a well grounded family structure, the sky becomes the limit. I salute the courage of Dr. Okanlami, the tenacity and the strong foundation of his parents in making sure he and his sibling didn’t lose their “Nigerianess”.

Well said, Patrick. I love how Dr. Okanlami emphasized that he, and indeed everyone else, can do all things through Christ who gives us strength.

I have shared this story with my children. It is a story of courage and triumph. We can all do whatever we are determined to do.

Thank you Sir. Such encouraging word goes a long way in letting all those showing such courage that they are not alone. Dr. Okanlami is an inspiration to us all.

This is such an inspiring story. I aspire to have his determination, courage, and confidence as I grow older and continue my studies.

Dr Okanlami story is beautiful and encouraging. The article has really inspired me and we love his connection with parents as well as his appreciation of the way they raised him.