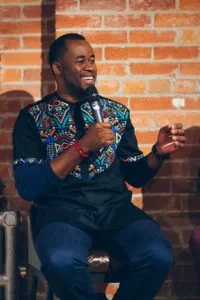

‘There is a lot to share with the world about the Igbo culture:’ ~ Chigozie Obioma

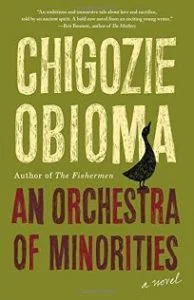

Many avid readers develop the skills to understand the plot, the protagonist, and the voices in a book within the first few sentences. But such is not the case when one reads Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities. The reason for this is that An Orchestra of Minorities is an unimaginable display of intricate narratives from the perspective of a person’s chi, a guardian personal god in Igbo cosmology.

In creating the dialogues, Obioma went where few African writers dare to go – the land of the gods – to unearth and display for his readers the complexities of Igbo cosmology and worldview. With his incredibly engaging prose, Obioma tried to answer the age-old question of why bad things happen to good people even when such people have surrounded themselves with good energy.

One only needs to read a few chapters of An Orchestra of Minorities to understand why the New York Times referred to Obioma as the heir to the great Chinua Achebe. Obioma’s stunning power of imagination arrests your curiosity from the first page and then takes you through labyrinths of an esoteric journey to the land of the gods and back. We invite you to read some of Chigozie’s thoughts in his own words as garnered from an NPM interview with Hamilton Odunze (NPM’s Editor-in-Chief) and Dr. Ejike Eze (NPM’s Editorial Board Chairman). Please share your feedback for the author and NPM in the comment section. Enjoy!

Nigerian Parents Interview with Chigozie Obioma.

NPM: Chigozie, thank you so much for accepting to speak with us today. We have been looking forward to this interview for a while. Our readers cannot wait to read your story. Let’s start by hearing a little about you. Who is the man Chigozie Obioma?

CHIGOZIE: I was born in Akure in Nigeria. I am from Abia State. My dad was a Central Bank staff. He was moved around a lot while I as growing up. At some point he got tired of moving around, so we settled in Akure until I was 17 or 18. Then we moved to Makurdi, which was where he retired.

I started writing very early. I wrote a widely-read personal essay for the New York Times in December 2018 (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/03/books/review/chigozie-obioma.html). In the essay I explained how my father used to drop me off at the library and leave me there for hours. I used to be very sick as a little boy and my parents would tell me stories all the time. This opened the landscape of my imagination. The more I heard the stories, the more I became more driven to create mine. So, the drive came from an obsessive desire to replicate what I was getting from the stories. That’s how I came to write.

After secondary school, I left Nigeria. I was going to go to the United Kingdom but eventually ended up in North Cyprus. I did my undergraduate studies there and finished as the number one student. They gave me a scholarship to do a master’s program. While doing my master’s degree, I completed my first novel, The Fisherman. I felt like North Cyprus was holding me back. I had this book and felt that if I could make a strong contact, I could publish it. That drove me to want to go to the United States or back to Nigeria. I applied to schools in the United States for an MFA in Creative Writing. Luckily, I got into almost all the schools I applied to. I went to the University of Michigan. It was in my first semester there that I sold my book. That’s how I came to be where I am today.

NPM: Your book is deep-rooted in Igbo culture, yet, it is written in very elegant modern prose: How did you gain so much insight into the Igbo culture?

CHIGOZIE: Curiosity number one. I was very curious. For instance, my name is Chigozie. I asked my parents what the chi in everyone’s names meant. My cousin was Chijioke, my brother Chinaza. So, what is this chi. My mom who grew up in a culture where she saw her dad go to pour libation to his chi, and ikenga every morning, was very conscious of these things. She told me all the stuff about the chi. I became interested in the worldview and cosmology of the Igbo. The more I studied it, the more I saw that it was a very complex system, probably even more complex than Christianity. In terms of complexity, you can compare it to religions like Hinduism. I do not necessarily practice the religion, but I just became more interested in it because of the way it informed the institutions in precolonial times.

It wasn’t just that we had the mythologies and cosmologies, our people created a world around these ideas just like other cultures did. If you look at the Western Judeo-Christian culture, for instance, and you look at the US constitution – things like all men are created equal, freedom of speech and liberal democracy – you can trace all these to the myth of Adam and Eve. It was the same thing for us. Because of the chi, there was not too many monarchical systems in Igboland. What the majority had was something like councils, where the oldest people – ndi ichie – came and met. I found out that the reason for that was because they believed strongly in the chi. If everyone has divinity, why would you create hierarchies where someone by virtue of birth would lord it over others? So, they had a sort of democratic system that was representative. Every family sends their oldest person to go and represent them at the village council. It was so democratic that you could not speak until the people agreed, hence the kwenu greeting. If the people say ekweghi m, then you must pause. You cannot continue until there is a consensus.

I looked at all that and realized that these people had this complex, well-thought out system of living. And we were thinking that they lived without much thinking. I even found out – and this is my own theory, which I have shared with several Igbo scholars – that the reason they were killing twins was not that they were evil. It is also because of the chi. If everyone was so unique that they had a spirit guide inside of them, something divine, then it is impossible that you can have a replica of that same person. So, they thought that the second of the twins was an evil clone of the first. So, they tried to find which one was the original and then they would discard the one they thought was the clone. It’s not like it was a good thing, but there was some rationale behind it. This is what I wanted the world to know, that there is this system and it is as sophisticated as you can find anywhere else. So, my novel, while it is a novel and is telling a story, I did not want to write non-fiction. So, in using it as a framework for the story, anyone encountering the story will also encounter the cosmology.

NPM: Nigerian Parents Magazine strives to help Nigerian Parents raise well-adjusted children. You are obviously well adjusted and have achieved so much. But before we talk about your phenomenal book, tell us about your parents and about your childhood.

CHIGOZIE: Again, it was the stories. My parents did not know what it will become for me. I wanted to be a football player. I played so much, and I would sustain injuries. We lived near a small river in Akure, which gave me the idea for my first novel The Fishermen. Because it was waterlogged with mosquitoes, I always had malaria. When I would get admitted in the hospital, I realized that I was not interested in watching TV or anything else. I would tell my parents to tell me a story. They would say close your eyes. Once I closed my eyes and listened to the stories, I would begin to imagine this world in the stories they were telling me. They would tell me stories from Achebe’s books, Shakespeare, Amos Tutuola and others. I believe they made me a writer without planning to. When I began to read a lot, they realized that that was what I wanted to do. I wrote my first novel when I was twelve. They became a little afraid because my other siblings wanted to do something better, become doctors, lawyers and all that. At some point, they started regretting it and wanted to stop me. They tried to get me to write on the side. They were afraid that in writing, there is no guarantee of being published and having a means of livelihood. They never said to stop but did not want me to waste my talent writing books in Nigeria where no one cares. They were very surprised when I called them to say that I had a book deal. And they were finally relieved when my book was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. They saw the coverage all over the world because no Nigerian had been shortlisted for the Booker Prize since Ben Okri in 1991. That was the transformative time. They realized the gamble paid off.

NPM: Writing a book is difficult. How do you have the discipline to sit down, dream up these great stories and write these wonderful novels?

CHIGOZIE: It has been a part of me for so long. Sometimes I wish I had become a footballer. Who knows? That too is a gamble. With the kind of work ethic, I have, I probably would have played for Barcelona. My work ethic is something I cannot do without. It has its own pleasures and challenges. I face them every day. I am distracted, even more so now that I have two children. But with all that, the thing that drives me again and again is that I really want to say something. I deeply care. My two novels are related in the sense that they are tackling Nigeria, the mess that is the country. I see myself as displaced. I would prefer to live in Nigeria. There is a part of me that is chronically sad because of the lack of progress in terms of national development. So, the situation of things in Nigeria drives me. Even when I say that I will sit back and not write, I will be forced to the page because there is a deep conviction to say something. People who succeed in writing are like that. There is a force that is beyond you, a pressure that you cannot resist. Even when it does not pay, you do it.

NPM: You speak about the work ethic, is there a family background or something else that helped you develop this incredible work ethic and drive to succeed?

CHIGOZIE: My dad especially. If there is a character in The Fisherman that resembles life, it is his character. He valued hard work and would reward it at every point. So, like most Nigerians, we were generally high-flyers. I am sure your children are top of their classes in their schools. The more my dad saw me reading, the more he encouraged it thinking it would help me develop intellectually. In the widely read New York Times essay i mentioned, there is a scene where I describe that I had begun to read so much that my dad got tired of buying me books and newspapers. So, he registers me at a local library. Every Saturday in the morning, he would take me there and pick me up around 2pm. All I would do was read. So, he really encouraged me. That kind of set me apart from my siblings. I was obsessive. I did not want to play anymore. I wanted to read and write.

NPM: You are already being referred to as heir apparent to the great. That is no mean feat. You have shown that you will be every bit as prolific as the great Achebe. What is the next book we should expect from you?

CHIGOZIE: They say that about everyone. I am working on a novel set in the past in Nigeria. It is a historical novel set in the 60s. I cannot wait to show it to readers. One thing to be prepared for is that it will be told in a unique way. It will be new to fiction again. It is also a family novel. So, I am returning to family in this new book.

I am also working on a few short stories, one of which my agent is about to send out now. It is one many people will like. It is kind of a metaphor for oil discovery in Nigeria.

NPM: All your books are written from a unique perspective. How do you create characters in your book?

CHIGOZIE: It is a mystery how these things happen. What happens is I get an idea, a topic, or a question that I want to explore. For instance, The Fishermen started from the phone call I had with my dad when I was in Cyprus. It was about my siblings who were always fighting when they were young. My dad told me that they have become best friends. After the call, I started thinking about the worst that could have happened during that time when they hated each other. Once I have a question like that, I picture characters and begin to explore. It begins with a mystery that I am trying to solve.

NPM: Can you talk more about The Ochestra of Minorities? Is it challenging to get people to understand it, especially those who are not of Igbo extraction?

CHIGOZIE: It is a challenging novel. In the US, publishers and media houses had difficulties finding reviewers for it. New York Times made a mess of it. They tried to get people to review the book and almost everyone declined to take on the challenge. They finally found a Ghanaian lady to do it. So, there is the struggle there. People ask why I would not write something more accessible. But I feel like this work needs to be done. We have all these cosmologies but there are no cosmological novels out of Africa. Someone must do the work. I feel like I am doing the dirty jobs of African literature. Those places where no one wants to go – our shrines, villages and psyche. It is what it is. But interestingly the book has done very well.

NPM: Tell us a little more about your family, the support system behind your success.

CHIGOZIE: I am married to an American. Her family is originally from Syria. We met on our first day at school in Michigan. She was coming in to start her doctoral program. I now teach at the University of Nebraska. We live in Lincoln. My family is very supportive. I have a brother in Indiana. I have two children. The older child is 19 months old.

NPM: Would you want any of your children to become a writer?

CHIGOZIE: No! The reason is that there are some complicated issues with writing that you don’t want your child to deal with. It is very subjective. There are people who can just come out and say whatever they like about your book. It does not have to be true. They just might not like the idea. There were editors that ignored The Fishermen when it came out, even when it was on the list for the Booker Prize. Some of the reviews were also hatchet jobs. Things like that can happen in writing but not in other professions. I would prefer they go into sports, but I am open to anything.

NPM: What else would you want Nigerians and NPM readers to know?

CHIGOZIE: As a parent, the possibility that any child we birth here will return to Nigeria is likely not there. The lineage is cut off from Africa. For me, that is a pain. It is an existential crisis to conceive that they will never be connected back to that source. So, I hope that parents find a way to make sure that that link is there. At the end of the day, whether this generation or the next, Africa must stand up. It cannot become a wasteland. Is it possible that even African Americans who want to return can have a first world black-only country that can absorb them? What if Nigeria can be that place? We need to raise a generation that will be conscious of the need to fight for our land. That is my message for the NPM readers.

NPM: Thank you for spending time with us, Chigozie.